|

The events of 1947-49, and specifically 1948 itself, are known as Al Nakba – the Catastrophe. It was the time of the forced expulsion of at least 750,000 Palestinians by Zionist militias, but has ‘the catastrophe’ now finished? Another year has now passed, this one marks the 60th since May 1948, and the pain is no less now than it was all those years ago. Once again May 15th has come around without answers and justice. Still millions wait for their rights. Still millions are forced to live crowded together in the refugee camps of Palestine and surrounding countries. But whilst some are marking this as the 60th year ‘since’ Al-Nakba, should we not be marking this as the 60th year of the ‘on-going Nakba’?

For whom has the catastrophe finished? Is it not true to say that forced expulsion continues unabated 60 years on, did the Apartheid Wall not again displace thousands upon thousands of Palestinians, and separate thousands more from their land, families, or even from remaining a physical part of the so-called West Bank? Is the ever-increasing expansion of Zionist colonies on Occupied land also not part of a steady practice of ethnic cleansing? What about the plight of the Bedouin of the Negev and other areas who continue to see their houses demolished and their land stolen? There is continued land theft of many shapes, itself a policy to strengthen the Zionist and Colonialist state whilst ‘encouraging’ indigenous Palestinians that they would be better of if they left since they have nothing left to stay for. And none of this takes into account the thousands of Palestinians killed, injured, and imprisoned of all ages. The catastrophe continues…

When I visited several of the depopulated villages last year I saw through the eyes of the beautiful children with whom I went quite what these villages mean, not just to those forced out in 1948 but also to every generation since. Amongst other villages we visited the beautiful village of Beit Jibreen. We saw the remains of the mosque and of Palestinian houses, we felt the space and breathed the air that is noticeable only in its absence in Aida Camp, and we tasted the delicious sweet Sabar fruit from the village’s ancient and immovable cacti before devoting our time to removing the razor-like thorns it left in our fingers. The children had heard so much of the villages from their parents and grandparents, the knowledge is passed on, yet none of the children had themselves lived through the experiences of 1948.

For Rowaidah AbdelRahman Al Azzeh, physical and very vivid memories remain to this day, and it is from the knowledge of her generation that today’s young Palestinian refugees have learnt so much:

“I was 12 years old when we were forced to leave Beit Jibreen, our home-village, in Oct 1948. This was five months after the creation of Israel and the big cruel massacre at Deir Yassin.”

The massacre at Deir Yassin was one of many. It saw over 100 Palestinians murdered in cold blood. Men, women, and children were slain by the invading Zionist militias, and those responsible used the horror of the massacre as a tool to force residents out of other villages, such as happened in Beit Jibreen:

“Residents of Beit Jibreen thought that they were safe until Israeli aircrafts flew over the village and dropped statements on pieces of paper. I still remember that day well; three aircrafts threw hundreds of statements printed on colored papers. I was the only one who could read in my family. My father brought me one of those statements which was written in Arabic and asked me to read: ‘To all residents of Beit Jibreen, you have only six hours to leave the village, if you do not leave, you will face the same end as Deir Yassin’. We fled to a nearby field where we stayed for one day and two nights. 20 to 30 men remained in Beit Jibreen with their hand guns to defend the village and protect the properties. A small battle occurred in which most of our relatives were killed so we fled to Hebron. Suddenly we became refugees, and stateless, with no home, no nationality, and no property. After sixty years of Al Nakba, we still live here, in a refugee camp, but we also still believe that we will return. And even if we die before our time, certainly our descendants will return....”

Rowaidah’s husband Mohammad also has stark images etched into his mind of what Beit Jibreen meant to the Al Azzeh family:

“Minutes before he died 40 years ago, my father told me, ‘you will not be able to take my grave to Beit Jibreen, but definitely you will be able to plant a tree…name it Hasan’s tree…’. After Al Nakba, my grandfather tried to return to our home village. He was caught three times by Zionist soldiers and forced to leave. On the third attempt he was led to the armistice line (the green line), shot in his leg, and told that he has to tell the others (Palestinian Refugees) that anyone who attempts to comeback would be killed. A year after his injury my grandfather died and was buried in Hebron. Days before his death, when I was just 14 years old, he told me ‘do you know why I was interested in teaching you? So you could take care of the 583 dunums we own in Beit Jibreen…when you return, take care of Um Alhaiyat’s land, the most fertile piece of land there…I paid too much to have it’.”

Mohammad is now 74 years old but his belief in return has not lessened with age, it is not something he would ever give up:

“Return for me means the existence itself; it is not only a piece of land, it represents our history, culture, humanity, and future. If I could not return then my grandson, Miras, has to plant two trees in Biet Jibreen! For sure, when he does so my soul will be there and will again be relaxed… even if my grave is still in Aida Camp.”

Generations pass away and continue to pass on these beliefs in ‘Return’, it doesn’t falter and it will never pass away as the Zionist entity had hoped all those years ago - they did not foresee the resilience of the Palestinian people or their nation. In fact, in many ways the belief develops as does the understanding of Nakba in the context of it being seen not as event from history but as something that maybe began many decades ago but continues to this day. Ask Mohammad’s grandson about Nakba and what it means to him and Miras will demonstrate the same articulation as the family patriarch but with a contemporary awareness and contextualization. He was one of the children through who’s eyes I had the honour of learning of Beit Jibreen last year. At just 14 years old Miras now talks of his understanding of the term ‘on-going Nakba’, and what it means to him:

“I heard the term ‘on-going Nakba’ several times before understanding and using it. In fact, my father uses it while he speaks to international visitors about Aida Camp where we live, about the Apartheid Wall which surrounds the camp, and about refugees’ rights. However I had never paid attention to the meaning of that term until Dec. 2006…”

Friday Dec. 8th 2006 is a day none of us will ever forget, and it is a day about which Miras thinks often:

“It was sunny as with most of Palestine’s days, but I will never forget it. We were seven kids, having some fun and playing in my sister’s bedroom before starting the final exams of the first semester. I was the oldest amongst us children at 12 years old, and the youngest was my cousin Ansam, she was only 3 years old. Since this day my family and friends have started to call me ‘lucky boy’. I became ‘lucky’ not because I won in Lotto, but because I did not die from the Israeli bullets shot by a soldier hidden in one of the watchtowers!”

The bullet that passed through Miras’ young body should have killed him according to the doctors who saved his life, but it didn’t. Miras again was just too full of Palestinian resilience and strength to give up. He is one of many thousands of Palestinians injured, much as his great-great-grandfather had been nearly 60 years earlier, and as several other family members have been in the years in-between. Miras has also seen and felt land confiscation and theft like his grandfather’s grandfather:

“Construction of the Wall around Bethlehem and Aida Camp has resulted in the confiscation of the Armenian Church land, that was the only space available to play in near Aida Camp. For me it was not only a piece of land; it was something I connected to as a human being, as a child I used to play football there. The on-going Nakba, and living as a refugee, has become clear for me. For me, on-going Nakba means continuous violations of my human rights, no peace, and no future.”

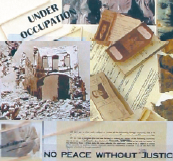

So today, May 15th 2008, is not just a day to commemorate a historical event. It is a day that marks 60 years of ‘on-going Nakba’ for the Palestinian people but not purely in the context of simple remembrance; it is a day to be retrospective but also a day on which to make proactive steps forward. For Miras and his grandparents, and for the millions of other Palestinian refugees, it is a day to continue and strengthen the struggle for ‘Return’ - for only when the day of Return comes can anybody, and inshallah everybody, find a real peace that is based on justice and not on the empty rhetoric of immoral politicians.

There can be no peace without justice. There can be no justice without return…

Rich Wiles is a photographic artist who has been living and working in Palestine for much of the last five years. His photography work has been shown around Europe, in the U.S., Australia and Palestine itself, amongst other places.

Since 2006 he has been writing from Occupied Palestine under the title 'Behind the Wall' for a forthcoming book. Much of this work is based in and around the refugee camps where he is based in Palestine, highlighting daily life and memories of refugees who still live in forced exile nearly 60 years after Al Nakba.

|