FAQ on the 1967 war

IMEU

30 May 2007

|

1. How did the 1967 war begin? The war began on the morning of June 5 with devastating Israeli air strikes on the Egyptian airforce, most of which was destroyed on the ground. Arab nations then came to Egypt's defense. Israel's first-day success brought air superiority which enabled it to decimate numerically superior ground forces.

2. Which countries were involved in the fighting? Israel, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Other Arab countries, including Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Algeria, contributed arms and small contingents of troops to the fighting.

3. What was the outcome? Israel quickly defeated the Arab armies, and seized the Syrian Golan Heights, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), the Gaza Strip, and the Sinai Peninsula. Israel's rapid victory stunned the international public. But Israeli and U.S. intelligence had both predicted an easy Israeli victory, even in a battle waged on multiple fronts.

4. How did Israel justify its attack? Israeli UN envoy Abba Eban initially claimed to the United Nations Security Council that Egyptian troops had attacked first and that Israel's air strikes were retaliatory. Within a month, however, Israel admitted that it had launched the first strike. It asserted that it had faced an impending attack by Egypt, evidenced by Egypt's bellicose rhetoric, removal of UN peacekeeping troops from the Sinai Peninsula, closure of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, and concentration of troops along Israel's borders. The Soviet Union introduced a resolution to the UN Security Council naming Israel the aggressor in the war. This resolution was blocked by the U.S. and Great Britain. Thereafter, the U.N. failed to rule definitively on the legality of Israel's actions, although it called for Israel's withdrawal from territories it seized in the fighting.

5. Is Israel's version of the facts universally accepted? Israel's claim of an impending Egyptian attack has been widely accepted in the West. The Israeli public had been led to believe that it faced a threat of imminent attack, and perhaps even annihilation. However, the veracity of Israel's claim is increasingly questioned. A number of senior Israeli military and political figures have subsequently admitted that Israel was not faced with a genuine threat of attack, and instead, deliberately chose war. Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli army chief of staff during the war, later stated: "I do not believe that Nasser wanted war. The two divisions he sent into Sinai on May 14 would not have been enough to unleash an offensive against Israel. He knew it and we knew it." (i) General Mattityahu Peled, a member of Israel's general staff in 1967, opined that "the thesis according to which the danger of genocide weighed on us in June 1967, and that Israel struggled for its physical existence is only a bluff born and developed after the war." (ii) Menachem Begin, not yet prime minister but a member of the Israeli cabinet, allowed that: "The Egyptian army concentrations in the Sinai approaches do not prove that Nasser was really about to attack us. We must be honest with ourselves. We decided to attack him." (iii)

6. If Israel's claimed reasons for the attack were false, what were its true objectives? One objective may have been territorial expansion. Some Israeli politicians and military leaders, such as former Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and Minister of Defense Moshe Dayan lamented the failure to seize East Jerusalem and the West Bank in the 1948 war. Before the war, Jordan's King Hussein told the American ambassador: "They want the West Bank. They've been waiting for a chance to get it, and they're going to take advantage of us and they're going to attack." (iv) Second, Israeli politicians were genuinely fearful of Gamal Abdul Nasser, the charismatic leader of Arab nationalism. They may have seen the war as an opportunity to embarrass him and deflate the movement he embodied. Third, Israeli leaders may have seen military confrontation with the Arab states as inevitable, and chose to engage in battle at a time and under terms of their choosing. Menachem Begin, for example, characterized Israel's war aim as to "take the initiative and attack the enemy, drive him back, and thus assure the security of Israel and the future of the nation." (v)

7. What was the chain of events leading up to the war? The progression toward war was sparked by Israel's attack on the West Bank village of Samu' in November 1966. Israeli forces, purportedly "retaliating" against raids by Palestinian guerrillas, killed 18 civilians and Jordanian soldiers, and razed nearly the entire village. After the attack, King Hussein bitterly criticized President Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt for "hiding behind" the UN Emergency Force (UNEF), stationed in the Sinai Peninsula after Israel's 1956 attack on Egypt, and failing to act in line with his Arab nationalist rhetoric. The criticism, echoed by the Arab press, drove Nasser into a more militant posture toward Israel. Tensions were also building between Israel and Syria, largely due to Israel's repeated attempts to farm in the Demilitarized Zone that had separated Israeli and Syrian troops since the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948-49. In April 1967, one such incident escalated into an aerial battle during which Israel shot down six Syrian fighter jets, including two over Damascus. The Soviet Union, at the time closely allied with Syria, then shared intelligence reports with Nasser that suggested an impending Israeli attack on Syria. The reports of major Israeli troop movements along the Syrian border were inflated, but not entirely inaccurate. In early May the Israeli Cabinet had authorized an attack on Syria, although the scope of it remained a matter of internal debate. Soviet exaggerations may have been designed to stir Egypt into a more aggressive stance in support of Syria, thereby deterring the feared Israeli strike. Nasser responded by requesting the removal of the UN Emergency Forces from the Sinai Peninsula, replacing them with Egyptian troops, and declaring the Straits of Tiran (leading from the Gulf of Aqaba into the Red Sea) closed to Israeli shipping.

8. Why was the UN Emergency Force (UNEF) only on the Egyptian side of the border and not on the Israeli side as well? The UNEF was established to maintain calm along the border between Egypt and Israel following the Israeli-British-French invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel declined the stationing of UN troops on its soil, while Egypt accepted them. Egypt held the right to request their withdrawal at any point. UN Secretary General U Thant, backed by the United States and Canada, responded to Egypt's lawful request by suggesting that UNEF be repositioned on the Israeli side of the border. This proposal to head off the growing threat of war was rejected by Israel. Israel also rejected U Thant's proposal to reinvigorate the Egyptian-Israeli Mixed Armistice Commission, an idea backed by Nasser. Additionally, the Egyptian president backed U Thant's proposal of a two-week moratorium on belligerent actions in the Straits and the appointment of a special UN representative to mediate between the two parties. Israel rejected both ideas.

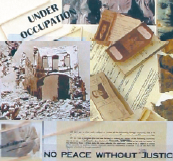

9. Where were Egypt's troops on the day preceding the war? Egyptian documents indicate that its troops were in a defensive posture in the Sinai and along the Suez Canal. Additionally, vital troops for any offensive remained in Yemen. Two Egyptian commando battalions joined Jordanian forces in the West Bank on June 3.

10. What role, if any, did the United States play in the diplomatic efforts to avert armed conflict? In the weeks preceding the war, the United States repeatedly warned Israel not to take unilateral action, and insisted on a diplomatic resolution to the developing conflict. The United States was urgently working diplomatic channels alongside UN Secretary General U Thant, attempting to avert war. The Egyptian vice-president was scheduled to meet with U.S. officials in Washington in early June. Two days before his visit, however, Israel struck. U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk said the United States was "shocked and angry as hell." (vi)

11. What were the consequences of the 1967 war for Palestinians? Palestinians suddenly faced the military occupation and settlement of their land. With the occupation came a dual system of law: one for Israeli settlers and one for Palestinians. The overwhelming military defeat of the Arab states also led Palestinians to conclude that their liberation would not be effectuated by the Arab states, but would have to be of their own making. This determination led to Palestinian resistance and significant outreach to the international community for political and economic support. Eventually, Israel's occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip became the primary focus of the Palestinian national movement, and other issues - such as the status of the Palestinian refugees from 1948, and the position of Palestinian citizens of Israel as an oppressed minority - were largely occluded.

12. What is the legal status of the land Israel seized in 1967? Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula pursuant to the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty concluded in 1979. Under international law, the other territories Israel seized in 1967 remain "occupied", and Israel is their "belligerent occupier." (vii) Israeli officials have often referred to the Arab territories it holds as "administered," or "disputed," arguing that unsettled claims of sovereignty to the West Bank and Gaza Strip free Israel of its obligations as an occupier under international law. That position has failed to find support in the UN Security Council, the UN General Assembly, the International Court of Justice, the International Committee of the Red Cross or the Israeli High Court. Israel evacuated its colonies from the Gaza Strip in 2005. Nonetheless, the Gaza Strip also remains occupied as Israel continues to maintain effective control over the region. Palestinians continue to require Israeli consent to (1) travel to and from the Gaza Strip from the West Bank; (2) take their goods to foreign and Palestinian markets and (3) obtain goods from Palestinian, Israeli and foreign markets. Israel also continues to maintain military control over Palestinian territorial waters and Palestinian airspace, while reserving for itself freedom of military operations in the Gaza Strip.

13. What were the long-term implications of the war for peace and stability in the region, and for the status of international law? International humanitarian law requires that belligerent occupiers protect the health, welfare and homes of the occupied civilian population. It also prohibits deportation of those living under occupation and the transfer of the occupier's own civilian population into the occupied territory. Israel has, for forty years, violated international law through its demolition of Palestinian homes, its deportation of thousands of Palestinians, its killing of Palestinians and its construction of Israeli-only colonies and roads. Though the UN Security Council, the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice have repeatedly criticized Israel's violations of international law, no effective action has been taken to halt the violations. The UN Security Council issued its opinion on Israel's actions in the following terms:

Footnotes: |

about us | links | contact us

| home

| register

© 2008 Australians for Palestine &

Women for Palestine